[Edit August 23, 2019: Please have a look at this new blog post if you are interested to craft your own brew water recipes ! ]

Introduction

In my first post, I mentioned how the water you use to extract coffee has a significant impact on the taste profile of your cup, in a way that does not necessarily depend on the taste of the water by itself. If you were using water just to dilute a cup of espresso (e.g., when making an americano), then your only worry would be that the water tastes good.

The key difference comes when you use water to extract coffee from the ground beans. In that situation, you want to have some potent mineral ions like magnesium (Mg+2) and calcium (Ca+2) that can travel inside the bean’s cellulose walls and come back with all the compounds that give the great taste to a cup of coffee. According to the Specialty Coffee Association (SCA), sodium (Na+) also plays a role, but a somewhat less important one. If you are wondering whether this is also true about tea – yes it is. If you live in Montreal, you might have noticed that you are unable to brew tea as good as the one you can drink at Camellia Sinensis, and your tap water is one main reason (they use mineralized water at Camellia Sinensis).

The Recommended Water Properties

In this post, I’d like to discuss extraction water a bit more, and give some practical tools for everyone to improve their brew water without necessarily needing fancy equipment. Let’s start by listing some of the SCA recommendations for brew water (I ordered them in my perceived order of importance):

- No chlorine or bad smell

- Clear color

- Total alkalinity at or near 40 ppm as CaCO3

- Calcium at 68 ppm as CaCO3 , or between 17–85 ppm as CaCO3

- pH near 7, or between 6.5–7.5

- Sodium at or near 10 mg/L

- Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) at 150 mg/L, or between 75–250 mg/L

The first two are more widely known, but it’s always good to keep in mind if you start creating your own mineral recipes (more on that later). If your resulting water is milky or has visible precipitation of minerals, it’s not good ! If this happens, you probably added way too much minerals for some reason. You can also easily get rid of chlorine by letting water sit on the counter for an hour or so.

Total alkalinity is often confounded with pH, but it’s not the same thing. pH measures the (logarithm) ratio of free OH– ions to H+ ions in a solution, with pH = 7 corresponding to a unit ratio (neutral). A larger amount of H+ ions produces a more acidic solution, with a lower pH, and a larger amount of OH– ions produces a more alkaline solution, with a higher pH. This is why total alkalinity is often confused with an alkaline solution, which is kind of understandable given this poor choice of terms.

Total alkalinity typically measures the amount of HCO3– ions, which are able to capture any free H+ ions that are added to the solution, and prevent them from making the solution more acidic by forming carbonic acid:

For this reason, HCO3– is termed an alkaline buffer in this context. A high total alkalinity will therefore make a solution more stable against pH changes. This bears some importance in coffee making, but there is a big problem with having a total alkalinity that is too high; it can react with the aromatic acids that were extracted from the coffee beans, and mask some of these important flavors. This is why the SCA recommends a very narrow range in total alkalinity near 40 ppm as CaCO3.

You may sometimes hear total alkalinity referred to as carbonate hardness. It’s a slightly different concept, but for coffee extraction water it’s almost always equal to total alkalinity (technically, this is true when the total hardness of water is higher than its total alkalinity).

At this point you may thinking “what the hell is this unit of measurement involving this random molecule CaCO3 ?”. Turns out scientists love to create large collections of weird measurement units, and this is yet another example of that (like measuring the energy of stars in ergs…). These ppm as CaCO3 basically ask “how many parts per million CaCO3 would you need to produce the observed HCO3– concentration ?”, which relates to this chemical reaction:

The next recommendation is to have calcium hardness between 17–85 ppm as CaCO3, with the units again relating to the same chemical reaction above. Magnesium is also widely used in the specialty coffee association, and is believed to extract slightly different flavors, but to my knowledge there are not yet any lab tests to back this up (there might be some blind testing backing it up, but I’m not aware of them). As a consequence, most people use a mix of magnesium and calcium as the extracting agents. I already explained the logic behind this recommendation above; you basically just want enough of these cations to do the extraction job properly, but not too much as to completely throw off balance the flavor of the coffee or to cause massive corrosion or scaling in your equipment.

Both of the magnesium and calcium cations are related to the total hardness of a solution, defined as the summed concentration of many cations (positively charged ions), among them calcium, magnesium, iron, strontium and barium. In coffee extraction applications, only magnesium and calcium are typically present, so total hardness is just taken as their sum. A more widely used recommendation would therefore be to keep total hardness in the SCA range, rather than just calcium hardness.

The next two recommendations are often not focused on too much in the specialty coffee community. I often see water recipes with pH in the range 8.0–8.2 (slightly alkaline), and the resulting coffee tasted great. I haven’t done extensive tests comparing pH~7 water to these recipes, as it’s typically hard to play with pH without affecting the other variables above. I also have not experimented much with the effect of sodium, so that could be the subject of a future blog post; for now, I just try to follow the SCA recommendation, but I don’t put too much focus on it.

A lot of people use tap water through a Brita to brew coffee. This is not bad in principle, but all such a carbon filter does is remove chlorine and other undesirable components, and soften the water (it decreases total hardness and total alkalinity). If this lands you in a good zone for brewing, that’s great, but it is rarely the case for typical tap water.

Visualizing the Water Options

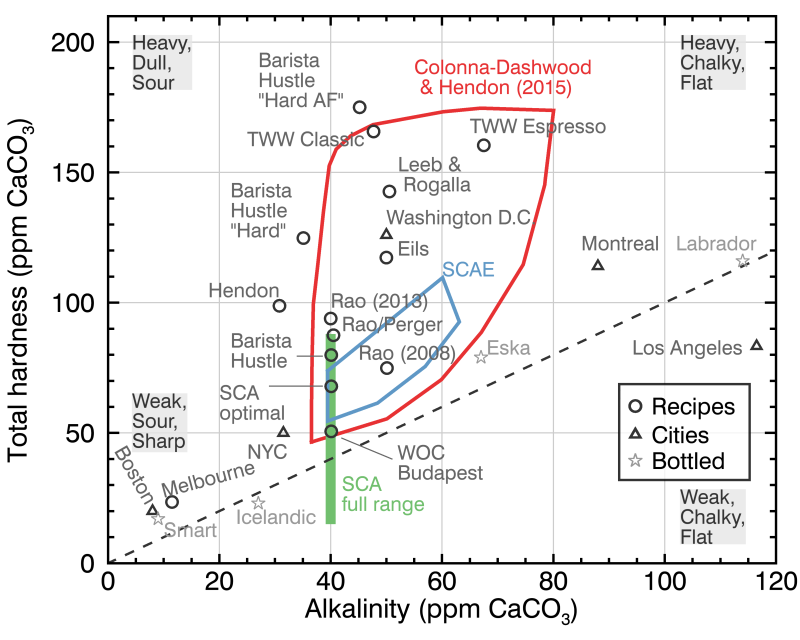

At this point, it would be useful to visualize the water properties of different cities, bottled waters and some recipes of coffee professionals:

In the figure above, you can see the range recommended by the SCA (green bar), the region recommended by the Colonna-Dashwood & Hendon (2015) Water for Coffee book (this mythical book is now pretty much impossible to find, but it is said by the ancient ones to go much deeper in the chemistry of coffee extraction than what I could ever write in this blog post), and the more constrained region recommended by the Specialty Coffee Association of Europe (SCAE), which is mainly based on avoiding regions of significant scaling (upper right) or corrosion (upper left), two aspects that are mostly important to the delicate internal parts of espresso machines. The Third Wave Water (TWW) classic and espresso profiles are little bags of pre-weighted minerals that you can dump in a gallon of distilled water to get easy water for coffee brewing.

The dashed line on the figure corresponds to a 1:1 total alkalinity and total hardness. Most naturally occurring water will fall near this line because of how water acquires its minerals by dissolving limestone. The widely used process of water softening by de-carbonization also moves the composition along this region (toward the origin of the figure). This is why a lot of city tap waters (triangles) and bottled waters (stars) fall along that line. I can’t believe that I lived for 3 years in Washington D.C. without ever knowing about any of this (and I Brita’d my water out of this great spot like a fool). You would be surprised how many of the city or bottled waters that fall completely outside of the range of this figure.

All other circles on the figure correspond to mineral recipes used or recommended by different professionals (e.g., the Leeb & Rogalla book, Scott Rao, Matt Perger, Dan Eils, the World of Coffee Budapest championship, the 2013 Melbourne World Barista Championship, and several recipes from Barista Hustle), the stars correspond to bottled waters, and the triangles correspond to different cities.

Practical Implementations

Now that we talked about the theory behind extraction water, we should focus on practical applications. You would be surprised how many specialty coffee shops have very expensive water filtration systems based on reverse-osmosis to rid the water of all its contents, and re-mineralization resins to achieve something close to these recommendations (try asking your favorite coffee shop).

At home however, none of this is really practical, as these devices typically cost several thousands of dollars, and still require you to monitor your tap water and adjust their setting from time to time. Unless you have the incredible luck of living somewhere with great brew water (the only example I know is Washington DC, at least in 2018), you have these types of choices (ordered by increasing effort required):

- Get a magnesium re-mineralizing water pitcher (e.g., the BWT).

- Order some third wave water minerals and dissolve them in a gallon of distilled water.

- Mix a pre-determined combination of bottled water brands.

- Buy distilled water and re-mineralize it yourself. This requires a bit more work but gives you incredible flexibility.

The BWT Pitcher

The first option has the merit of being simple, but you have almost no control over the final result. A BWT pitcher will soften your water and then add in some magnesium, which will move you toward (0,0) and then upward in the figure above. I don’t know to what extend it moves the composition around, so ideally you’ll want to test the result with some aquarium water hardness and alkalinity kits. I suspect the result would be decent in cities with similar compositions to Montreal.

Third Wave Water

I found that third wave water (the “classical profile”) produces a really good result for very little effort. You do have to buy a gallon of distilled water, which is a bit of effort, but they are extremely cheap and will last for a dozen cups of coffee. The “espresso profile” of third wave water is useful if you are worried about scaling and corrosion in your espresso machine, so I recommend only using it for espresso, not for filter coffee. I compared a Colombian coffee (the Ignacio Quintero from Café Saint-Henri) extracted with third wave water, the Rao/Perger and Dan Eils water recipes (discussed more below) by blind tasting, and I found the third wave water to be a bit overwhelming in term of resulting acidity.

My guess is that this is due to third wave water being much higher than the other recipes in terms of total water hardness. I preferred the Rao/Perger recipe, but in all honesty all three cups were very good, and way better than what you get with Montreal tap water. I think third wave water is also a good option for traveling, as it comes in a little sealed package with the composition marked on it, so that might not cause problems at TSA (although I have not tested this yet). You would still need to buy a gallon of distilled water though, so depending on the nature of your trip this could be a non-ideal solution.

I must confess, I am not sure I placed the Third Wave Water points on the right position of the “total alkalinity” axis. This is because they use a less usual component called “calcium citrate”, or Ca3(C6H5O7)2 in their mix of minerals. Once dissolved in water, each of these molecules will liberate three Ca+2 cations and two C6H5O7-3 citrate anions (negatively charged ions). I treated each of these citrate anions as an alkaline buffer that can capture three H+ cations each, and assumed that they are stable enough as citrate acid (C6H8O7) to prevent a significant pH change. This is a lot of assumptions, and I also needed to assume that citrate acid is as efficient at actually capturing the H+ cations as are the HCO3– anions. Once I made these assumptions, I just calculated what amount “ppm as CaCO3” of HCO3– would have the ability to capture the same amount of H+ cations. It is quite interesting that the classic profile falls quite close to other brew water recipes in total alkalinity when making all these assumptions.

[Update, January 3 2019: I have now tested the total alkalinity of Third Wave Water (classic profile) with a Hanna Instruments photometer, and obtained a measurement of 43 +/- 5 ppm as CaCO3 total alkalinity; this is very close to the ~ 50 ppm as CaCO3 that I had predicted ! It could be slightly lower because citrate anions may be slightly slower or worse at capturing H+ cations, but this is almost within the measurement error so I would not deduce too much from this measurement alone. The main point is: citrate anions do act as an alkaline buffer, and third wave water is exactly at the SCA-recommended value for total alkalinity !]

Bottled Water

Mixing water bottles or distilled water is another viable option. If you use a combination of two bottled waters, you can imagine a line drawn between the two stars that correspond to each of the bottled water properties in the figure above, and different mixing ratios will place you at different spots along that line. Using three bottled waters instead of two will allow you to move on a triangle-shaped surface that connects the three bottles in the chart. A problem with a lot of bottled waters is that they are not far above the 1:1 total alkalinity vs total hardness line (the dashed line in the chart), making it harder to fall anywhere in the Colonna-Dashwood & Hendon (2015) region. The lack of bottled waters high in total hardness and low in total alkalinity limits the use of three-bottled combinations.

From the little data gathering I have done yet, I found that using a water really high in both total alkalinity and total hardness (like Montclair water) mixed with much softer water is a good way to go. Here are a three bottled water recipes that seem to work great (with their designated letter on the next figure):

(A) The Montclair/Smart recipe

Right now, the best 2-bottled combination I could find is 10 parts Smart Water to 1.6 parts Montclair. This will place you at a total alkalinity of 40 ppm as CaCO3, and a total hardness of 69 ppm as CaCO3, nicely split between calcium (17 mg/L) and magnesium (6 mg/L). It will even include 5 mg/L of sodium, falling a bit short but not that far from the SCA recommendation.

(B) The Montclair/Distilled recipe

Another great option is to mix 10 parts distilled water with 2.05 parts Montclair water. This is very similar to the last recipe, but slightly softer (67 ppm as CaCO3), and with a bit more sodium (9 mg/L), extremely close to the SCA recommendation in sodium.

(C) The Smart/Compliments recipe

If you can’t get your hands on Montclair water, try this one: 10 parts Smart Water with 1.6 parts Compliments. This will get you something a bit softer in total hardness (57 ppm as CaCO3), still with a mix of calcium (14 mg/L) and magnesium (5 mg/L), but without sodium.

I have not tried tastings with these bottled water recipes yet; this was determined just from calculations. Let me know if you try them before I do !

If you would like to experiment with some more mixes of bottled water, I created a Google Sheet here, which I will keep updating in the future. You can do File/“Make a Copy”, and then you’ll be able to add in some more bottled water and create new recipes. You can also find many more mixed bottle water recipes that I fiddled with in there.

Another viable option may be to mix your tap water with distilled water, but this will only allow you to move along a line connecting (0,0) to your city in the first figure, and you would ideally need to monitor seasonal variations in your tap water hardness and alkalinity. I added a few tap water compositions (Montreal, Laval and Washington DC) in the bottled water spreadsheet.

Mineral Recipes

If you want to take things to the next level, you can get yourself some minerals, a scale precise at 0.1 g or better (mg-precision scales are not too expensive; I use this one and I really like the small plastic dishes that come with it), some mason jars, and a pipette or a small kitchen plastic spoon. There are a total of five minerals you will need if you want to do all of the recipes below, but the simpler ones can be done with just the first two in this list. For the less common items, below I will give you some Amazon links that I used to buy them.

Please make sure you always buy food-grade ingredients, not the pharmacy-grade or lab-grade ones. The latter two may be more pure than food grade is, but the rare impurity could be much worse for your health (e.g., heavy metals). Barista Hustle mention that pharmacy-grade epsom salt is probably ok to consume at these low concentrations, but I consider the key word here to be “probably”, especially if you’re going to drink this every morning. Once you opened a bag of minerals, always keep them in a cool, dry place in a hermetic jar, especially those in anhydrous form.

Notice that epsom salt is not simply MgSO4, but rather its heptahydrate form MgSO4•7H2O, which makes it look like a clear crystal. MgCl2 and CaCl2 can be found both as hydrates or anhydrous (no water) forms. Some vendors don’t specify what form they are providing, which can be annoying, but in general if you have little white spheres of CaCl2 they are probably anhydrous, and if you have milky clear crystals of MgCl2 they are probably of the hexahydrate from (see pictures below). It’s ok if you don’t get the exact hydrate form, but you’ll need to adjust the weights to get the same amount of Ca+2 or Mg+2 cations.

After doing some research on the web, I could get my hands on a dozen mineral water recipes. I have not tried them all yet, but I will comment those that I did try. I modified all recipes below to make them more uniform. In all cases, you’ll need to put the specified weights of minerals in a jar that can hold 200 mL of water (ideally slightly more). A glass jar such as a regular mason jar is good for this, and I would avoid metallic containers because of potential corrosion.

Once you put the required minerals in the jar, add in some distilled water until you hit a total weight of 200 g. This will be your concentrate; a solution often white that will initially degas some CO2 and will easily precipitate solid minerals. I recommend keeping such a concentrate in a cool dark place for a few hours with the mason jar lid just slightly screwed, to allow for the outgassing to complete. You might even stir it up a few times to help things get going. You will also get a much faster reaction and outgassing if you use warm or hot distilled water, but I am not sure if this affects the resulting composition (I don’t think it does, and my first trial with the Rao/Perger recipe and hot distilled water turned out great).

Your concentrate will be good for 50 liters of water. This is a lot of water. Think of it like this: you can fill a very big bath with amazing coffee with that much water. In other words, I highly recommend (1) not going crazy and starting up 8 different 200 mL concentrates when you first read this, and (2) keep them tightly closed in the fridge after they degassed. If you want to compare several water recipes, you can create downsized versions of the concentrates without problem (use a rule of three to downsize both the concentrate volume and mineral weights by the same factor).

Once you have a concentrate, I recommend putting it on your scale, taring the scale, and using the pipette or small plastic spoon to scoop out 16 g and put it in a 4 L of distilled water (or 4 grams per liter). Congratulations, this is your mighty brew water. Make sure you keep it in the fridge, especially when it is almost empty, and always smell it before using it. As I mentioned in my last post, if it smells like an old rag, so will your coffee. In my experience, a gallon of distilled water will turn bad after approximately a week out of the fridge, or a month in the fridge. This is a much slower staling process than what you would get with tap water, as distilled water starts out free of any bacteria. I also don’t really recommend letting the water sit in your boiler for more than a few hours, but this is definitely less an issue when you started with distilled water as a base.

Now, here are the recipes !

The Rao/Perger Recipe

-

- 5 g epsom salt (MgSO4•7H2O)

- 2 g MgCl2•6H2O (hexahydrate) or 1 g anhydrous MgCl2

- 1.5 g anhydrous CaCl2 or 2 g CaCl2•2H2O (dihydrate)

- 1.7 g baking soda (NaHCO3)

- 2 g bicarbonate potassium (KHCO3)

Reference: Scott Rao

Comments: So far this is my favorite recipe from blind testing.

It produces a bright and well-balanced cup.

[Edit May 11, 2019: Please note that this concentrate (and perhaps others on this page) will precipitate some white salts. This is perfectly normal and it will not precipitate once diluted with distilled water into your brew water. Just make sure that you mix the concentrate thoroughly until no deposit is left at the bottom every time before you use it.]

The Dan Eils Recipe

-

- 5 g MgCl2•6H2O (hexahydrate) or 2.3 g anhydrous MgCl2

- 3.8 g anhydrous CaCl2 or 5 g CaCl2•2H2O (dihydrate)

- 5 g bicarbonate potassium (KHCO3)

Reference: Scott Rao’s Instagram post

Comments: This is a great and simple recipe.

So far, my 2nd best favorite from blind testing.

The Matt Perger Recipe

-

- 10 g epsom salt (MgSO4•7H2O)

- 3.4 g baking soda (NaHCO3)

Reference: This website.

Comments: I have not tried this one yet.

The Rao 2013 Recipe

-

- 4 g MgCl2•6H2O (hexahydrate) or 1.9 g anhydrous MgCl2

- 3 g anhydrous CaCl2 or 4 g CaCl2•2H2O (dihydrate)

- 3.4 g baking soda (NaHCO3)

Reference: I deduced this one from other recipes above.

Comments: I have not tried this one yet.

The Melbourne Recipe

-

- 2.9 g epsom salt (MgSO4•7H2O)

- 1.0 g baking soda (NaHCO3)

Reference: The Barista Hustle simple DIY recipes.

Comments: I have not tried this one yet.

The World of Coffee Budapest Recipe

-

- 6.2 g epsom salt (MgSO4•7H2O)

- 3.4 g baking soda (NaHCO3)

Reference: The Barista Hustle simple DIY recipes.

Comments: I have not tried this one yet.

The Barista Hustle-Simplified SCA Optimal Recipe

-

- 8.4 g epsom salt (MgSO4•7H2O)

- 3.4 g baking soda (NaHCO3)

Reference: The Barista Hustle simple DIY recipes.

Comments: I have not tried this one yet.

The Barista Hustle Recipe

-

- 9.8 g epsom salt (MgSO4•7H2O)

- 3.4 g baking soda (NaHCO3)

Reference: The Barista Hustle simple DIY recipes.

Comments: I have not tried this one yet.

The Barista Hustle-Simplified Rao 2008 Recipe

-

- 9.2 g epsom salt (MgSO4•7H2O)

- 4.2 g baking soda (NaHCO3)

Reference: The Barista Hustle simple DIY recipes.

Comments: I have not tried this one yet.

The Barista Hustle-Simplified Hendon Recipe

-

- 12.2 g epsom salt (MgSO4•7H2O)

- 2.6 g baking soda (NaHCO3)

Reference: The Barista Hustle simple DIY recipes.

Comments: I have not tried this one yet.

The Barista Hustle Hard Recipe

-

- 15.4 g epsom salt (MgSO4•7H2O)

- 2.9 g baking soda (NaHCO3)

Reference: The Barista Hustle simple DIY recipes.

Comments: I have not tried this one yet.

The Barista Hustle Hard “AF” Recipe (i.e., “Hard as Falcon”)

-

- 21.5 g epsom salt (MgSO4•7H2O)

- 3.8 g baking soda (NaHCO3)

Reference: The Barista Hustle simple DIY recipes.

Comments: I have not tried this one yet.

I also collated all of these recipes in another Google sheet, which you can also play with if you do File/“Make a Copy”. That one will estimate the resulting total hardness and alkalinity from the input recipes, as well as other detailed quantities. You can also use the Aqion website to get the same outputs for the simpler recipes (maximum 3 minerals, and the calcium citrate present in Third Wave Water cannot be included). A nice aspect of the Aqion website is that it also gives you the electric conductivity (EC), in the units of μS/cm (microSievens per centimeter) often measured by cheap TDS-meters (TDS is for total dissolved solids). This is a great way to double-check that you didn’t mess up your brew water, but always make sure you measure it at 25°C. Even when TDS-meters say they do a temperature correction, it’s a bad one. I would also not trust the TDS reading itself, because these instruments make important assumptions on the actual composition of your water to translate the EC to a TDS.

Happy brewing ! In BOTH senses 😀

Special thanks to Alex Levitt and fungushumungous for proofreading.

[Edit May 30 2019: If you’d like to read more about brew water recipes, head over here to Mitch Hale’s blog !]

References

- Scott Rao’s blog and Instagram (both contain a wealth of information).

- The Barista Hustle website.

- The Specialty Coffee Association

- Special thanks to Scott Rao, Charles Nick and Victor Malherbe.

Hello Jonathan, thank you very much for the detailed article. I have had excellent results with the SCA Water according to your recipe. Can you confirm it will be safe in an espresso machine’s stainless steel boiler, especially in terms of corrosion? If not, what water would you recommend? Thank you!

LikeLike

Hey ! I have not yet included corrosion or scale calculations, so I would recommend using this water crafter by David Seng to verify that: https://www.espressoschool.com.au/coffee-water-calculators/

LikeLike

You can found on the NACE Standart about corosion.

LikeLike

I’ve added an entirely new Corrosion and Scale calculator. It will predict scaling and/or corrosivity potential and rates of scaling precipitation.

LikeLike

Thanks! That’s great

LikeLike

Hello!

– Is the API GH and KH test kit (link below) the easiest/best way to validate my Rao Perger water? The results appear to provide GH/KH per PPM in increments of ~17. Is that sufficently accurate?

– No need to also get the PH or any of the other tests, correct?

– If I’m trying to narrow down the cause of my muted brews despite upgrading to the Forte, would it be easier to switch temporarily to Third Wave Water until things stabilize or is the KH/GH test a great starting point?

– grind size distribution anaysis in progress!

Thanks as always for the tips!!!

LikeLike

Yes titration kits are a good way to go. Please see my new Q&A page there’s a more detailed answer that I won’t repeat here. No need to check pH. Also yes third wave water is a good way to debug; is not as god as Rao/Perger but it’s decent.

LikeLike

Thx! Did that. You said to just check KH but the GH test was included so I checked and it was about 11 off from your target. That’s within spec, right? KH was about 5 off. Took the tests with 10ml rather than 5ml samples as you had suggested to.

LikeLike

Yeah I usually just check KH because I just want to make sure I put the right amount of concentrate in my bottle and that the concentrate didn’t sediment too much (eg if I didn’t shake it properly). That’s totally within spec, the error bars are ~9 ppm as caco3 for a 10 mL sample, and differences this small probably wouldn’t have a big effect on taste anyway

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was suspicious that making the concentrate using a 0.01 gram instead of 0.001 gram scale would screw things up a bit, but apparently it worked out! Your blogs/videos etc are super helpful and appreciated.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nah 0.01g is fine. Thanks!

LikeLike

hello Jonathan, thank you so much for sharing all these informations with us! I have a question about the above recipes: they are concentrates, right? (Sorry if I just missed something!) In how much distilled water do we put the minerals for the concentrate and then what is the ratio to put in a 4L jug for instance? Thank you so much in advance for your reply!

LikeLike

Hi Daniel, they are concentrates, and how much of the concentrate is needed for a 4L jug depends on the recipe – For most of them, I designed the concentrate so that you need 16g per 4L jug. This is column K in the spreadsheet, i.e. weight (g/L). a 4g/L concentrate weight means you need to add 16 grams of concentrate per 4L jug.

LikeLike

Hi Jonathan, thanks a million for making this so accessible and easy. I just mixed up some Rao/Perger water yesterday. Sure enough, the concentrate has deposits at the bottom. I’ve chosen to remineralize in 1L bottles, which also have some minerals settling at the bottom after I add my 4g of concentrate. Do you have any recommendations?

LikeLike

Hi Mike, deposits are perfectly normal with the Rao/Perger concentrate. Just shake well before use.

LikeLike

Big thanks! It performed well this morning, winning in a blind taste test vs. San Francisco tap water.

LikeLike

Hi Jonathan,

Thanks for sharing so much detail and really helping along those looking to enhance their coffee!

I was wondering if you could point me to some resources or offer some guidance on making brew water with direct mineral addition and not concentrate solutions. At my current stage of experimentation I would prefer to avoid making concentrate bottles and simply make recipes by weighing out the various minerals directly into an empty gallon jug. The problem is that almost all of the discussion I find on water recipes focuses on concentrates. Can you help with recipes on a per gallon basis with direct mineral addition? I’m not looking for conversions on all the popular recipes just a couple to start with. I currently have calcium chloride, epsom salt and baking soda.

Thanks so much,

Jonathan

LikeLike

Cheers Jonathan, earlier on this comment site, Jonathan Gagne recommended the free water calculator at Espressoschool’s homepage to me, he also sent a link. I have been using that calculator ever since, it also offers the possibility to enter the desired amounts of Ca, Mg and Alkalinity in ppm CaCO3 along with the amount of brew water you want to make, and it will output the exact mg amounts of epsom salt, CaCl2 etc.

I have been getting 5l jugs of distilled water from the store and adding minerals directly according to the calculator. Be advised though, when doing direct dosing, the amounts are very very small so I would highly recommend getting a mg scale.

Hope this helps

LikeLike

Thanks so much! Yes, I have a mg scale.

LikeLike

As Luke mentioned, make sure you use a mg scale – and also shake thoroughly and wait several hours before using your brew water. The concentrate helps speed up dissolution into the final gallon of water, and here you won’t benefit from that.

LikeLike

Great advice. Thanks

LikeLike

Do you brew coffee from Tim Wendelboe? If so, would you recommend using the Melbourne water recipe?

LikeLike

I do brew Wendelboe coffee sometimes, but I also use Rao/Perger water for it. I haven’t tried Melbourne water.

LikeLike

Hey Jonathan,

I’ve been making this brew water for around a year now. I bought a cheap water TDS & PH meter from Amazon, and I am getting high PH readings (8.5) and low TDS readings (90-110ppm). Also, with TDS readings, I can’t seem to get a consistent reading. I am quite meticulous in my water prep, basically to the one-thousandth of a gram, and I am rinsing and cleaning things with distilled water. So my questions is, are the readings unreliable or is there something I should double check and keep an eye out? Thank you.

LikeLike

The readings are unreliable. Please see my more recent post about measuring water properties, I talk about it.

LikeLike

Hello! First off thanks for all the great coffee info. You mention that you wouldn’t let the water sit in your boiler for more than a few hours. Do you have any recommendations on how to accomplish that? I have a dual boiler machine with the combined boilers housing about 2L of water. Not sure if there’s a non wasteful way to purge the total contents either before or after brewing

LikeLike

I agree the coffee made from Third Wave Water classic profile is strongly acidic, would it become closer to the alkalinity and hardness of Rao/Perger water by adding more distilled water? How much?

LikeLike

I don’t have any good options for Distilled water, but plenty of nearby stores have RO water machines.

Is there any (rough) advice you would give, for translating these (distilled water) recipes to work for R.O. water?

LikeLike

Yup absolutely. Some RO water machines can also get you down to 10 ppm or less, which is really so close to distilled that you might not even have to worry about it. But I have a spreadsheet in one of my water blog posts that allows you to craft water starting from non-distilled. It just has to be relatively stable over time, and softer in both GH and KH than your goal recipe. Also, the lower ppm the RO gets you, the less the output’s gonna vary if your tap water varies.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks. I am going to buy a GH KH test kit (API’s aquarium kit) to get the GK and KH of my RO water source to use in your water crafting tool. Do you have any advice for what to put for the ions for the input RO water? My understanding is RO will remove most ions, but don’t know enough to know whether “just go with 0” is close enough.

LikeLike

I always find water the most puzzling, complex part of coffee. Question: if most tap water has a lower level of HCO- than Mg+ and Ca+, and when water is boiled all the HCO- ‘pairs up’ with Mg+ and Ca+ (forming limescale), how can there be any HCO- left in the water to reduce its acidity?

LikeLike

This effect of scale formation does not happen instantly. If you wanted all of the Mg and Ca to pair with HCO and precipitate out of your water, you would have to boil it for a very long time in the kettle. If you did so, you would indeed end up with no HCO left to react with your coffee, and in practice your brew water would probably behave like KH~0, lower-GH water, and you would have a lot of scale in your kettle.

LikeLike

Hello Jonathan. I am using a 5 gallon jug with a flowjet pump with BWT Bestmax Premium filter (Mg+) that feeds my Fetco XTS commercial brewer. I am filling the jug with tap water with the following specs: Ca hardness = 86ppm, total alkalinity = 75, pH =7.4, phosphate = 800 ppm, GH = 8, KH=6, TDS = 300 (note these specs were measured at a pool store). My brew water after passing through the BWT filter is GH = 6, KH= 4 (on bypass setting 1 out of 0-4). I do not have same pool store specs on actual brew water. I’ve brewed over 600 liters of coffee with the brewer and honed in the brew specs (using Scott Rao’s recommendation and sprayhead) over the last 7 months for best taste. I’ve used quality coffee, many different light-med roasts, I use a baratza Forte BG grinder, and 204F temp. The resulting coffee has consistently had a weak body. It’s near weak sour sharp. Even at a 14.5:1 brew ratio with 3 liter batch brews, the body and flavor are still lacking. For a ballpark recommendation, what minerals can I try adding to my 5 gallon of water to try and improve the extraction/taste? Note that the BWT Bestmax premium exchanges Ca+ in water for Mg+. I am using bypass setting 1 which is about 70% of water is getting mineral exchanged but all the water is getting filtered. Thanks.

LikeLike

It looks like the average CaCO3 in my city (Winnipeg) is almost exactly where that Eska bottle water is, which just shy of being within the recommended range. Would I see much difference in experimenting with this or is my water probably okay? I appreciate the advice!

Alkalinity, Total parts per million as calcium carbonate average: 69.7, range: 62.3 to 83.7

Hardness, Total parts per million as calcium carbonate average: 81.4, range: 77.6 to 90.8

https://winnipeg.ca/waterandwaste/water/testResults/WaterTreatmentPlantTreated.stm

LikeLike

Thanks a lot for all the great information!

Here in Israel we don’t have any food trade distilled water and all the distilled water available for buying has a warning “not for consumption”. Do you think that’s a problem or when adding the minerals and boiling there shouldn’t be any risks?

LikeLike

Hey ! Sadly, this would *not* be safe. This warning can be caused by the presence of heavy metals which will still be there after boiling and can be toxic. You will either need a RO system, or a pitcher like the Zero Water to get distilled water.

LikeLike

Thanks!

Is there a way to check for these metals?

LikeLike